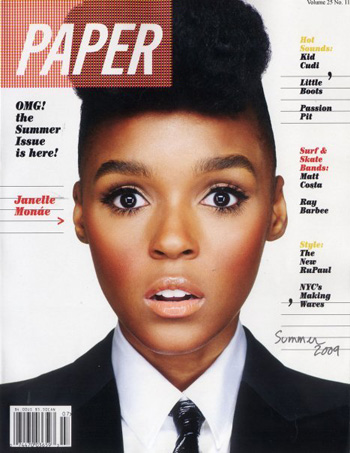

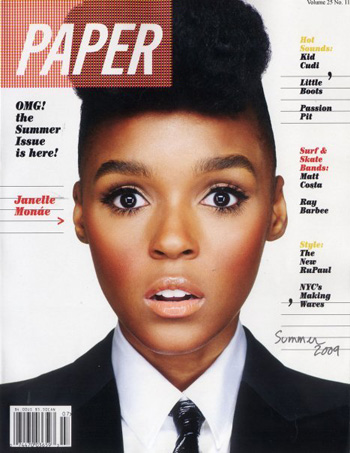

by Laura

Show me a man who looks better in a tux than Janelle, I dare you

Jess’s post on the performance of masculinity coincided nicely with another piece of reading on my plate this week, a memoir by SF novelist Samuel R. Delaney called The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village 1960-1965. I started reading Delaney’s book because I am studying his ex-wife, Marilyn Hacker’s, poetry, and she is a major figure in the memoir. What I didn’t expect was that it would be, in addition to a chronicle of what was clearly an exciting and strange time and place to be a young artist, an enthralling read about masculinity and sexuality. Delaney is a gay black man who married a white Jewish woman when they were both teenaged aspiring writers, trying to figure out how to be who they were in a pre-Stonewall, pre-Civil Rights Movement bohemian New York. It’s all pretty fascinating, but the passage that struck me most last night was this, in which Delaney struggles to understand how the incredible personal and social power he finds in then-illicit sex (cruising Central Park, bathhouses, docks, etc.) fits in with his daylight life:

It’s even hard to speak of that world. But looking back on that morning and the mystical ambiguities that seemed so important to it, I saw that such moments were themselves largely social and psychological illusions — unless you realized what they meant was that forces both social and psychological were at work to pull you toward the most conservative position you might inhabit, however poorly you might be suited for it.

The mystic experience was a psychological sign that you’d reached a cul de sac where it was too exhausting to separate the personal from the social on the most conservative level. It was as an exhortation to vigilance against this muddying phenomenon that, I suspect, a few years later, the radical slogan “The Personal is the Political” was formulated. (242-3)

Now, I’m not a person who’s had much in the way of mystic experience. But this is one of the clearest and most concise social critiques I’ve ever read:

forces both social and psychological were at work to pull you toward the most conservative position you might inhabit, however poorly you might be suited for it. I think this is true for all of us; the difference in how people experience it lies in the last clause: however poorly you might be suited for it. Some people are well suited to inhabiting a conservative social position; many are not. But we are all under extreme and constant pressure to do it anyway, to move not just to the center but to the far poles of “proper” behavior. This is why there is a difference between performative masculinity and straight-up

menaissance feste misogyny: calling it “irony” is too shallow, but that’s part of it. It’s a question of how you inhabit your body and the social role that kind of body is ordered to occupy.

I am a cis queer/bi woman and thus most of my experience of this has to do with femininity. My desires are queer and my femininity is shot through with masculinity. When I was a miserable unpretty teenager, that felt like a failure. As an adult, it feels like a social and psychological victory: a refusal of traditional femininity and its interleaved misogyny, not a fiasco of it. That’s the biggest difference between being an adolescent and being an adult woman, for me — I get to reclaim what felt like failure as a victory instead.

Defying norms feels like work because it is, because of those forces trying to pull you toward the most conservative position you might inhabit. That is why refusing to perform femininity seems like more work to so many women than the actual work of femininity, which is

more labor-intensive but also hidden. That is why accepting your body is

so much harder, at first, than

fighting to “

better” your body — because, like horrible

magnets, those forces pull you backwards. We all must keep “vigilance against this muddying phenomenon” if we want to feel that our performance of gender matches our desires. If that’s not a priority for you, so be it. But if it is, well, strap in: we have a lot of work to do.